July’s birthstone, Rubies embody the color of love, passion, and romance, possessing a rich history, potent symbolism, and popularity spanning over 2,500 years. Discovered in 1991, Songea, Tanzania’s most prolific Corundum (Ruby & Sapphire) area is intermittently mined. Named for its famed locale, Songea Ruby’s naturally beautiful burgundies, magentas, and maroons, also feature desirable, uncannily high-clarities. Far rarer than its rare Sapphires, these gorgeous crystals were long-vaulted until their 2024 lapidary. Unlike most Rubies that are enhanced, they’re just faceted, making them far scarcer, more valuable, and extraordinarily unique.

Hardness 9

Refractive Index 1.762 – 1.778

Relative Density 3.97 – 4.05

Enhancement Heat

Beauty

Songea Rubies display bright, intense purplish-reds with a gorgeous medium to medium-dark saturation (strength of color) and tone (lightness or darkness of color). While visually ‘pure’ reds are highly-prized, Rubies are dichroic (two-colored: purplish-red and orangey-red) pleochroic gemstones; even the ‘finest’ Rubies are only around 80 percent pure, with secondary orange, pink, purple, or violet.

Songea Ruby looks beautiful when viewed in both natural and incandescent light, the rarely obtained gemological ideal. This is the exact opposite to their Corundum cousin, Blue Sapphire, who loathes incandescent light. While some Rubies strongly fluoresce in natural light, Cambodian, Thai, and Songea Rubies lack this feature, due to their high iron content. Even though Rubies’ are one of the world’s most expensive gems, as usual, quality determines price. With Rubies coming in many different colors and sizes, personal preference should be the ultimate concern. While color preferences are subjective, for the professional, the intensity and purity of Ruby’s signature reds are the primary factor in determining value.

As transparency and inclusions also affect Ruby’s beauty and subsequent value, Ruby is clarity classified by the GIA (Gemological Institute of America) as a Type II gemstone (some minor inclusions that may be eye-visible). Maintaining both beauty and quality, our Songea Rubies were optimally faceted in April, 2024 in the legendary gemstone country of Sri Lanka (Ceylon), home to some of the world’s very best Corundum lapidaries, and most likely Rubies’ original locality. Each crystal was carefully orientated to maximize colorful brilliance, maintaining a high/mirror-like polish (accentuating its vitreous ‘glassy luster), an attractive overall appearance (outline, profile, proportions, and shape), and an eye-clean clarity (the highest quality clarity grade for colored gemstones as determined by the world’s leading gemological laboratories). Optimal lapidary in Ruby negates color unevenness due to zoning (location of color in the crystal versus how the gem is faceted) and excessive windowing (areas of washed out color in a table-up gem, often due to a shallow pavilion).

Named from the Latin ‘ruber’ (red), Ruby and Sapphire are color varieties of the mineral Corundum (crystalline aluminum oxide), which derives its name from the Sanskrit word for Rubies and Sapphires, ‘kuruvinda’. Trace amounts of elements such as chromium, iron, and titanium, as well as color centers, are responsible for producing Corundum’s rainbow of colors. While many red gems were called ‘Ruby’ until the development of scientific gemology in the 18th century, during antiquity, Ruby, Garnet, Spinel and other red gemstones were collectively called ‘carbunculus’ (‘little coal’ in Latin). Known as ‘anthrax’ (live coal) to the ancient Greeks, these gemstones were beautiful deep red gems that became the color of glowing coal embers of a fire when held up to the sun, noting Sri Lankan Rubies may have been available to the Greeks and Romans as early as 480 BC via ancient trading routes. Carbunculus is ‘carbuncle’ in English and this word was also once used to describe all red gemstones. For example, in the King James Bible, Ruby and its namesake ‘carbuncle’ score several mentions. Not surprisingly, the historical allure, legends, lore, mystique, and myths surrounding one of the most precious of gems is as colorful as its beautiful red hues. The mighty ‘Rubinus Lapis’, the red stone, Ruby is also the oriental ‘Gem of The Sun’, and as mentioned in Sanskrit texts, ancient Hindus were so enchanted by the color of Rubies that they called them Ratnaraj ‘The King of Gems’. Ancient Indians believed Ruby to possess an internal fire that not only endowed long life, but could even help you bring the kettle to the boil! In the Middle Ages, Rubies, like so many other gems, were believed to possess prophetic powers, deepening in color if bad moons were rising. Worn by ancient Burmese as a talisman to protect against illness, misfortune or injury (not surprising, considering their ‘blood-like’ color), Rubies were once known as ‘blood drops from the heart of mother earth’. In the 19th century, Ralph Waldo Emerson penned one of his famous poems, describing Ruby as, “drops of frozen wine from Eden’s vats that run” and “hearts of friends, to friends unknown”. A couple of antique terms used to describe Ruby color that are still sometimes used include, ‘pigeon blood’ (a rare and valuable, traditionally Burmese Ruby color), which is confusingly once again back in fashion, and ‘beef blood’ (richer reds, perhaps somewhat reminiscent of red Garnets).

Rarity

Far scarcer than Diamonds, Rubies are extremely rare, and one of the rarer better-known gemstones. Highly-coveted, Rubies are among the world’s most expensive gems, and the ‘big red’ in the ‘big four’ quartet, along with Diamond, Emerald and Sapphire. Ruby origins include, Afghanistan, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia, China, India, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, and Vietnam. A major international gemstone hub, Thailand is the transit point for approximately 90 percent of the world’s Rubies as they journey around the globe.

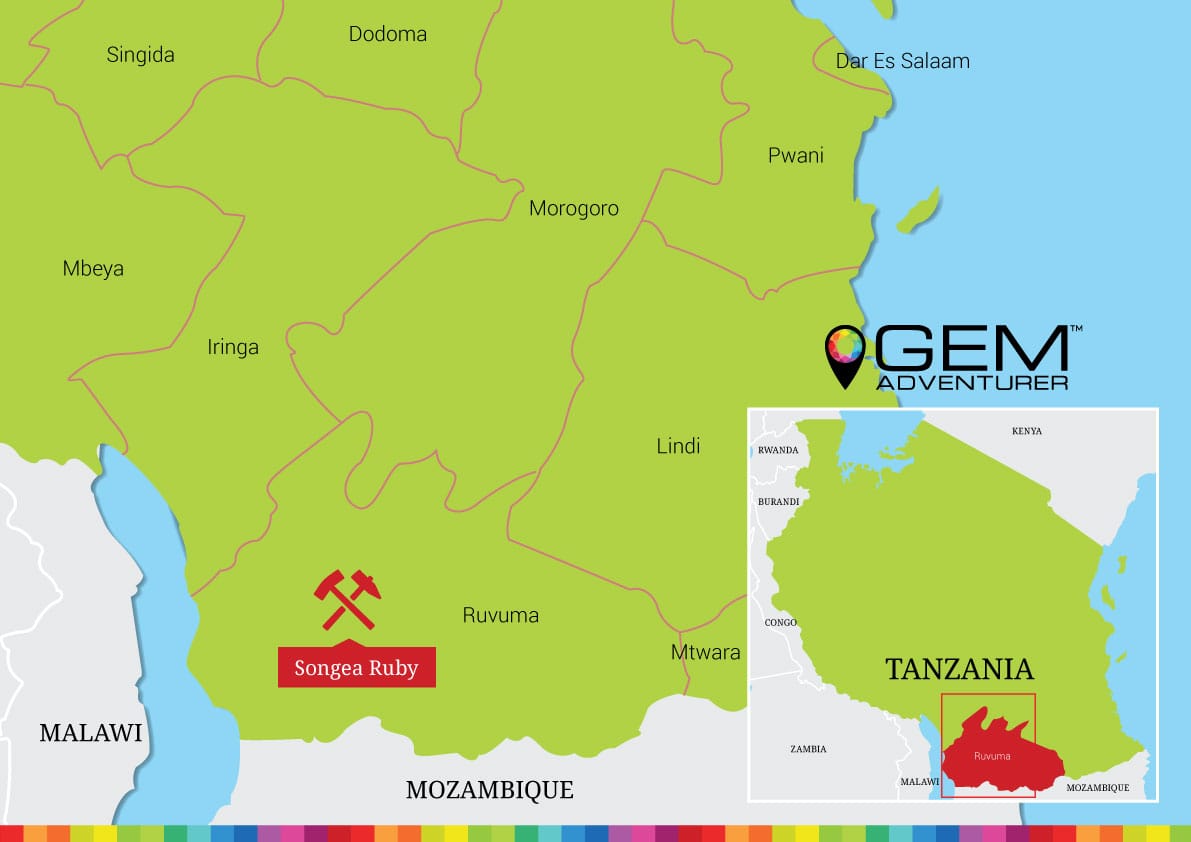

East Africa’s largest country and home to Africa’s highest peak (Mount Kilimanjaro), Tanzania is also a vital source for Corundum. Located alongside the mineral-rich fields and mountains of Mozambique and Zambia, Tanzania’s abundance of gemstones, and specifically Corundum, is geologically due to the Mozambique Orogenic Belt, one of the world’s richest. Orogeny is the process of mountain formation, usually by the earth’s crust folding. Tanzanian Ruby’s main deposits include, Longido (1914 – 1915/1924), Morogoro (1970), Mahenge (1986), Songea (1991), and Winza (2007).

Songea Ruby is from important deposits first discovered in 1991 by a rice farmer, located about 60 kilometers west of Songea town in Tanzania’s Ruvuma Region, centering around Masuguro and Ngembambili villages. With the first crystals sold to Thai gemstone dealers at Tanzania’s capital, Dar Es Salaam, by 1992 miners rushed to Songea to try their luck at this country’s latest ‘gem casino’, swelling the population by more than 10,000! With foreigners often unwelcome at the mines, downtown Songea became the second most important Tanzanian gem trading town after Arusha, home to Tanzanite. Only very occasionally yielding red-dominant Ruby, Songea corundum contains high magnesium, resulting in a wide variety of fancy colors. While usually blues to greens to yellowish, with some purples to reds, and occasional color change, since 2002, Songea Corundum is often high-temperature beryllium enhanced, artificially creating vivid oranges, orangish-reds, and yellows.

While Songea is historically Tanzania’s most fruitful Corundum locale, mining rushes and levels vary over time, depending on sporadic, pocket discoveries (recently, February 2024), with most activity today small-scale, both artisanal or mechanized. Far rarer than its rare Sapphires, Songea Ruby like all sole source gemstones possesses a genuine rarity, with natural calibrated parcels, largely historic (pre-beryllium enhancement, 2002), limited, and challenging to obtain. With Thai miners and buyers active in the Songea marketplace, most of its Corundum is destined for enhancement. This is understandable given how well it responds to both modern and traditional treatments, but also regrettable, noting many will never experience Songea Rubies’ natural beauty.

An old mine parcel from a heavily-worked area, its smaller, ball-shaped alluvial crystals faceted gems below 7x5mm, with an excellent 29 percent calibrated cut yield, well-within the usual gem mineral return (20 – 35 percent). Thankfully, our Songea Ruby is also one of the few gemstones that are totally natural and unenhanced, accentuating desirability, rarity, and value. Well-over 90 percent of Rubies are permanently heated to alter their color and/or improve color uniformity and/or appearance.

Defined as any process other than cutting that improves a gems’ appearance, durability, value or availability, 90 percent of all gemstones in the marketplace have been enhanced in some manner. As these processes have become an important part of the modern gem industry, enhancements are acceptable as long as they are disclosed, permanent, and stable. While gemologists can often spot indications of gemstone enhancements, advanced scientific testing is frequently required for confirmation and absolute certainty. Becoming malleable around 1900°C and melting at 2030°C, Rubies can withstand incredible temperatures. Rubies also have no cleavage (i.e. very high toughness), allowing them to endure high temperatures with an acceptable breakage risk.

Heating Rubies to improve clarity or develop color has been used in some form for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Likely practiced in the sub-continent over 4,000 years ago, heating is one of the earliest known gemstone enhancements. Early references to the heating of gemstones include Pliny the Elder in his ‘Naturalis Historia’, c. 77 AD and two Egyptian papyri dating to the third or fourth century AD. The scientist Abu Rayhan al-Biruni not only developed the specific gravity scale, using it to identify many gemstones, but in his book, ‘The Book Most Compressive in Knowledge on Precious Stones’ (circa 1048 AD) he describes in detail the 1100°C heating of Corundum to remove dark colored areas. Interestingly, this is basically one of the same methods still used today.

Referred to as ‘traditional’ or ‘standard’ heat, modern ‘low’ temperature enhancement involves heating Rubies to 1200°C – 1700°C for anywhere up to an hour to 36 hours, often repeating the process to achieve the desired results.

While almost all Rubies are heated, this is not always a simple ‘traditional’ process that originates in antiquity, with new techniques continuously being developed (e.g. heating with pressure, circa 2009). Often a sophisticated process that has taken experienced specialists’ decades to perfect, high temperature heating can significantly change a Rubies’ original appearance (and value). For example, modern electric and gas furnaces can heat Rubies to 1800°C (close to their melting point) for up to seven days, sometimes with this being repeated numerous times. These high temperatures allow the incorporation of additives, such as glass (filling cavities and cracks) and coloring agents (e.g. beryllium bulk diffusion to dramatically alter color). As these enhancements radically change the color and clarity of arguably inferior gemstones, Rubies that have been heated with additives should be disclosed, and not simply described as ‘heated’.

Durability & Care

The world’s second hardest gemstone (Mohs’ Hardness: 9), Songea Ruby is an excellent choice for everyday jewelry. Songea Ruby should always be stored carefully to avoid scuffs and scratches. Clean with gentle soap and lukewarm water, scrubbing behind the gem with a very soft toothbrush as necessary. After cleaning, pat dry with a soft towel or chamois cloth.

Map Location

Click map to enlarge