Named for its locale, Australian Hartsite is a beautifully unique Zircon exclusive to the Northern Territory’s Central Harts Range Fossicking Area. Given its famous deposits in Cambodia, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania, fine antipodean Zircon is extremely scarce and virtually unknown outside Australia. Prized for its superior quality and brilliant hues, Australian Hartsite elegantly combines gorgeous peachy champagnes and pinkie peaches with its highly desirable, signature diamond-esque optical beauty. Unearthed 30 years ago, Australian Hartsite is incredibly rare, extremely limited, and not readily available in jewelry, making it highly collectable for connoisseurs of fine Australian gemstones.

Hardness 7.5

Refractive Index 1.810 – 2.024

Relative Density 3.93 – 4.73

Enhancement Heat

Beauty

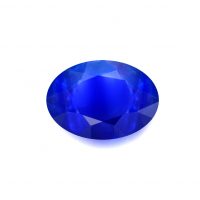

Australian Hartsite wonderfully displays a constantly shifting fusion of beautiful beiges, orangish-yellows, pinks, and yellowish-oranges, with a highly desirable light medium saturation and tone.

Afforded by its high refractive index, Australian Hartsite has excellent brilliance and scintillation (play of light), approaching Diamond (2.02 vs. 2.42), the most brilliant natural gemstone. Incomparable in the gem kingdom, Australian Hartsite’s high fire also significantly boosts its gemological beauty and value. Fire (dispersion) is the splitting of light into its component colors, and the most dispersive gemstones ranked in order are Sphalerite1, Sphene2, Demantoid3, Diamond4, and Zircon5. With a diamond-like (adamantine) luster, the highest non-metallic luster, Australian Hartsite also beautifully reflects a high percentage of surface light. Lastly, Australian Hartsite is strongly doubly refractive, light splitting into two rays as it passes through the gem. Extremely attractive, this is immediately visible as a doubling of the facets, resulting in beautiful sparkling mosaic patterns and optical depth.

To maximize its inherent beauty and optical properties, Australian Hartsite requires optimal lapidary and an eye-clean clarity, the highest quality clarity grade for colored gemstones as determined by the world’s leading gemological laboratories, with an excellent finish, proportions, and shape.

Zircon has been found in some of the world’s oldest archaeological sites, which is no surprise given the mineral’s durability. Incredibly, a tiny 4.4 billion years old fragment of Zircon discovered at Jack Hills in Western Australia is the oldest mineral formed on earth. Perhaps it should be said that ‘Zircons are forever’!

A popular gemstone for nearly 2,000 years, Zircon is rich in history and legend, appearing in several ancient texts, including the Bible and the Hindu poem of the mythical Kapla Tree, which was bejeweled with leaves of Zircon and gifted to a god. Some sources mention a Jewish legend that names the angel Zircon as the guardian appointed to watch over Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Called by its ancient names, Ligure and Jacinth, Zircon gets several mentions in the Bible. Firstly, as one of the ‘stones of fire’ (Ezekiel 28:13-16) that was given to Moses and set in the breastplate of Aaron (Exodus 28:15-30) and secondly, as one of the 12 gemstones set in the foundations of the city walls of Jerusalem (Revelations 21:19). Andreas, the Bishop of Caesurae, who wrote in the late 10th century, was one of the earliest writers to link the apostles with the 12 gems of Jerusalem. He associated Jacinth (Zircon) with the Apostle Simon. According to its mythology, Zircon represents purity and innocence. Like so many other gems whose changes in their colors or luster are said to be indicative of their wearer’s mood, health or fate, Zircon’s loss of luster apparently means danger is looming.

As a jewelry gemstone, Zircon has enjoyed several peaks in popularity. In 16th century Europe, Italian jewelers heavily featured Zircon. Later it was also fashionable in Victorian jewelry, but it wasn’t until the ‘roaring 20s’ that Zircon got its first taste of modern popularity.

A gemstone since antiquity, Zircon is one of December’s birthstones. The gem name ‘Zircon’ was coined in 1783 by Abraham Gottlob Werner from the evolution of two etymologies; one is the Arabic ‘zarkun’ (red), another the Persian words ‘zar’ (gold) and ‘gun’ (color). However, don’t be confused by the colors indicated by its word origins. Zircon comes in an array of colors, including blue, champagne, cinnamon, coffee, cognac, golden, green, honey, orange, red, saffron, turmeric, white (colorless), and yellow. It also has an assortment of historical and commercial names, which can be confusing. Mentioned by Axel Cronstedt in 1758, Jargon is pale yellow; Jacinth is red and was named by Georgius Agricola in 1555; Hyacinth is yellowish-red (or perhaps even blue), and is from ‘Hyacinte’, named by Barthelemy Faujas de Saint-Fond in 1772; Matara Diamond or Ceylon Diamond is white; Starlite or Siam Zircon is blue; and Ligure, originally named ‘Lyncurion’ by Theophrastus in 300 BC, is apparently generic. Lastly, a gem that may have been today’s Zircon was called ‘Chrysolithos’ by Pliny the Elder in 37 AD. Unfortunately, Zircon is often unfairly confused with the inexpensive synthetic Diamond simulant, cubic zirconia. While their names sound similar and White Zircon was once regarded as an excellent Diamond alternative, this is where any similarity ends. Zirconium oxide was discovered in 1892, but it wasn’t until 1937 that cubic zirconia was discovered in its natural state. In nature, cubic zirconia’s crystals are way too small to be cut as gemstones, so the two German mineralogists who made the discovery didn’t even think the mineral important enough to give it a formal name. In the 70s, Soviet scientists at the Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow perfected growing cubic zirconia crystals in a laboratory. They named the jewel ‘fianit’, but unfortunately for Zircon, the name didn’t catch on outside the USSR. The institute published their results in 1973 and by 1976, cubic zirconia was being produced commercially under the trade name ‘djevalite’. By the 80s, cubic zirconia was mass marketed as the Diamond substitute of choice. Gemstones are formed within the earth, not a laboratory. Remember, for a gem to be a gem it must be beautiful, durable and rare. As they can be made anytime, man-made gems are not rare, so are these ‘impostors from the factory’ even really gems? Zircon is a real gemstone and cubic zirconia is not, please don’t confuse the two! Widely distributed, mineral Zircon is found in most igneous and metamorphic rocks and is also common in sedimentary deposits, being the most frequent constituent of most sands. Zircon’s hardness, high melting point (over 2500°C), and metals (zirconium and hafnium), see it widely used in a variety of industrial applications. While analyzing Zircon’s composition in 1789, Martin Heinrich Klaproth, a German chemist, discovered zirconium. This metal was then isolated from Zircon in 1824 by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, a Swedish chemist.

Rarity

While Australia has the world’s largest Zircon mineral reserves (approximately 35 percent with over 320 recorded deposits), and mines more Zircon than any other country, this is ostensibly all industrial – very few crystals are gemstone quality.

Typically found alongside Sapphires, Australian Zircons’ main gem-quality sources are the alluvial deposits in eastern Australia (New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania) weathered from basaltic volcanic rocks. Several locales in New South Wales, especially the Sapphire fields of the New England area, for example Kings Plains, sporadically yield beautiful Zircons, but in minuscule quantities. The Northern Territory also occasionally yields limited amounts of attractive Zircons at a handful of locations in the Central Desert Region, including Harts Range, and the Mud Tank field near Alcoota Station, arguably Australia’s best-known fossicking location for gem-quality Zircon.

Hailing from a fossicking area located due south of the Atitjere Community, Australian Hartsite has been collected by artisanal miners, fossickers, prospectors and rock hounds since the 50s. Mined in the early 90s, approximately 30 years ago, our Australian Hartsite is historic artisanal mining, gathered by a small, socially responsible, mine-to-market collective, with exceptional value afforded by vertical-integration. Extremely important in today’s gem and jewelry industry, nothing is lost to unnecessary middlemen, and provenance is assured. While the miners have access to several locations in the area, most crystals are heavily fractured and generally included, making them unsuitable for faceting. The cut yield for Australian Hartsite is also very low, less than 2 percent, noting the typical return on a gem mineral is 20 – 35 percent.

Durability & Care

Australian Hartsite (Mohs Hardness: 7.5) is an excellent jewelry gemstone well-suited to everyday wear. Always store Australian Hartsite carefully to avoid scuffs and scratches. Clean with gentle soap and lukewarm water, scrubbing behind the gem with a very soft toothbrush as necessary. After cleaning, pat dry with a soft towel or chamois cloth.

Map Location

Click map to enlarge