A uniquely beautiful gem with a fascinating history, Russian Demantoid are brilliant, intense, forest green gemstones from Karkodino in Russia’s Southern Urals. With gemstones, beauty drives demand and rarity price. The sheer beauty of Russian Demantoid is incredible and its genuine rarity frustrating. One of the rarest and most desirable gems, Russian Demantoid is among the most valuable and highest priced colored gemstones. Noted for its high quality, Russian Demantoid’s beautiful color, impossible rarity, and signature ‘diamond-esque’ properties make it a prized addition to any jewelry collection.

Hardness 6.5 - 7

Refractive Index 1.888

Relative Density 3.70 - 4.10

Enhancement None

Beauty

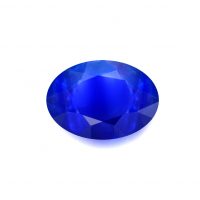

Long regarded as producing the finest quality, Russia is Demantoid’s original source. Russian Demantoid has intense, bright, medium ‘emerald-forest-greens’ that are not too dark (brownish) or too light (yellowish). Its beautiful color aside, Russian Demantoid possesses unique optical properties that significantly contribute to its beauty; an adamantine (diamond-like) luster, extreme scintillation (sparkle), and a fire (dispersion, the splitting of light into its component colors) greater than Diamonds. Demantoid has the highest fire of all the Garnets; its dispersion is 0.057, making it even higher than Diamond’s (0.044). The most dispersive gemstones ranked in order are Sphalerite1, Sphene2, Demantoid3, Diamond4 and Zircon5. Fantastic fire adds both beauty and value, resulting in exceptionally brilliant gemstones with a spectacular brightness.

All our Russian Demantoid is faceted at the miner’s own cutting house in Yekaterinburg (Ekaterinburg), the fourth-largest city in Russia and the capital city of the Urals. Yekaterinburg was founded in 1723 by Tzar Peter the Great (and named after his wife, Empress Catherine II; later named Sverdlovsk by the Soviets). Since the early 19th century, Yekaterinburg experienced a growth in the fine art of gem-cutting, for which the Royal Ekaterinburg Lapidary Factory was largely responsible. Today, Russian lapidary is highly regarded and well-known for its quality. While Demantoid is classified by the Gemological Institute of America as a Type II gemstone (some minor inclusions that may be eye-visible), the marketplace standard is an eye-clean clarity, the highest quality clarity grade for colored gemstones as determined by the world’s leading gemological laboratories. Demantoid’s ‘diamond-like’ luster and its extreme scintillation contribute to its amazing brilliance, and this is dependent on expert lapidary. All our Russian Demantoid’s are faceted by experienced cutters who employ high quality diamond-lapidary techniques to craft truly beautiful gems with excellent brilliance, eye-clean clarity, and an attractive appearance (finish, outline, profile and proportions), regardless of shape. While Russian Demantoid is usually faceted as oval, round brilliant or cushion cuts, other shapes are also available.

When Demantoid first hit the jewelry marketplace its spectacular beauty secured its popularity. An important gemstone in high-end Victorian jewelry, Demantoid had its greatest impact in its homeland of Imperial Russia. Quickly becoming a mainstay of the Tsar’s court jewelers in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, Demantoid was even a favorite of that famous Russian goldsmith, Peter Carl Fabergé. Demantoid might have been the ‘Tsar’ of Russian jewelry, but its dominion also spread much further afield; it was a big hit with early French fashionistas and even the legendary George Frederick Kunz (chief gemologist for Tiffany & Co.) travelled to Russia to purchase Demantoid. But for Russia, change was on the horizon and during the Soviet era, without supply, demand eventually dwindled, and a once popular gem was temporarily relegated to history’s sidelines. Thankfully, the recommencing of small-scale Demantoid mining in Russia around 1991 and its discovery in other countries has revitalized interest in this gem’s many appealing qualities.

Used in adornment for over 5,000 years, Garnets were popular in ancient Egypt from around 3100 BC, being used as beads in necklaces as well as inlaid jewelry (gems set into a surface in a decorative pattern). Garnet’s many myths frequently portray it as a symbol of light, faith, truth, chivalry, loyalty and honesty.

In Judaism, a Garnet is said to have illuminated Noah’s Ark and Garnet (carbuncle) was also one of the gems in the ‘breastplate of judgment’ (Exodus 28:15-30), the impetus for birthstones in Western culture. Crusaders considered Garnet so symbolic of Christ’s sacrifice that they set them into their armor for protection. In Islam, Garnets illuminate the fourth heaven, while for Norsemen, they guide the way to Valhalla. A Grimm’s fairy-tale even tells of an old lady, who upon rescuing an injured bird was rewarded for her kindness with a Garnet that glowed, illuminating the night.

Demantoid and the Grossular Garnet, Tsavorite are the two green varieties of the Garnet family. Demantoid was discovered (1849) and named (1855) by Dr. Nils Gustaf Nordenskjöld, the same gemologist who identified Alexandrite. Dr. Nordenskjöld took its name from the old German ‘demant’ (diamond-like), in reference to Demantoid’s optical properties. Due to color similarities, Demantoid was originally assumed to be Emerald and then mistakenly sold as Chrysolite. From the Greek for ‘golden stone’, Chrysolite is the old name for Peridot. While Dr. Nordenskjöld undoubtedly made a correct species determination, this gem originally had several common and incorrect names in the early days of its discovery. These include Bobrovka Garnet, Siberian Chrysolite, Ural Chrysolite, Ural Pearls and Uralian Emerald. In 1871 Russian mineralogist V. P. Yeremeev confirmed Demantoid to be the green variety of Andradite. Andradite Garnet is named after Brazilian statesman José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva (1763-1838), the first geologist to give it a description. Generally shades of orange-brown (cognac chocolate oranges), Andradite gets it’s many colors from the replacement of iron by aluminum and chromium and the replacement of calcium by iron, magnesium and manganese. Its colors include black, brown, colorless, green, gray, orange, red and yellow. Black Andradite is called Melanite (from the Greek ‘melanos’ meaning black, it was historically used for mourning jewelry), Yellow Andradite is called Topazolite (named for its visual similarity to Yellow Topaz), and Green Andradite is known as Demantoid. Andradite sources include Afghanistan, Iran, Italy, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Pakistan, Russia, Sri Lanka, the U.S.A., Uganda and Zaire. Like Emeralds, Demantoid is colored by chromium and/or iron, ranging in color from bright green (forest greens) and yellowish green (grass greens) to yellow-green (savannah or canary greens), although bluish greens and greyish greens are sometimes encountered in Africa. Iron causes yellow in Andradite, but when the iron is substituted by chromium (the Midas element that gives so many gemstones their signature hues) it appears as various shades of green. If there is any iron remaining in the Demantoid it will appear yellowish or yellow green. January’s birthstone, Garnet’s name is derived from the Latin ‘granatus’ (from ‘granum’, which means ‘seed’) due to some Garnets’ resemblance to pomegranate seeds. Coming in blues, chocolates, greens, oranges, pinks, purples, reds and yellows, Garnets are a group of minerals possessing similar crystal structures, but varying in composition, giving each type different colors and properties.

Rarity

Demantoid’s original source was in Russia’s central Urals in primary (host rock) and secondary (alluvial) deposits along the Bobrovka River and the Sissersk District (including the famed Kladovka deposit, one of the original finds still being worked today).

Demantoid is today mined in Iran, Italy, Madagascar and Namibia, but as Russian Demantoid still exhibits the purest and most intense greens, it remains the marketplace standard. While Demantoid mining began in Namibia in 1993 (most of the claims lying west of the Erongo Mountains in the Namib Desert), the exact date of its discovery remains a mystery, though it was most likely during German colonization. A Namibian Demantoid specimen dated 1936 is in the collection of the British Museum. Namibian Demantoid has less chromium (but more vanadium) than its Russian cousins. Discovered in the early 70s, Demantoid is also found in northern Italy and, since 2002, Iranian Demantoid (unearthed near Soghan, Baft District, Kerman Province) has hit the marketplace. Initially confused as Green Zircon or Green Sapphire, Demantoid has also been recently discovered in northern Madagascar. Hailing from a deposit near the village of Antetezambato (about 20 kilometers northeast of Ambanja), Demantoid from this locale was first identified in 1922. Despite this early recognition, mining only began in March 2009.

While the fall of the Soviet Union saw many of the original deposits in Russia’s central Urals reworked, new Russian Demantoid deposits were discovered in the 90s including Karkodino, Kamchatka, Chukotka and several other small deposits in the Novouralsk region.

Our Russian Demantoid is mined at the Karkodino (also Korkodinskoe, Karkodinskoe or Novo-Karkodinskoe) deposit located near the town of Korkodin in Russia’s Southern Urals in the Ufaley (Ufalei) district of the Chelyabinsk region. The surrounding forests are thick and swampy, with Korkodin station located right between the cities of Verkhnii Ufalei and Poldnevaya. The gems are mined from open pits, going directly to Yekaterinburg for grading and lapidary. Official documents date the discovery of Karkodino to 1991, but this deposit was actually worked during the Soviet era, but abandoned with all documentation lost. Mining Russian Demantoid remains challenging; due to cold winters the mining season only lasts approximately six months per year, with most mining occurring from around May to July. With the majority of gems mined smaller than 1 carat, Russian Demantoid one to two carats in size are extremely rare, a fine Demantoid over 2 carats is exceptional and anything over 5 carats is a museum specimen.

Karkodino is noted for producing beautiful bright green Demantoid that does not require any additional enhancement. It is the only primary deposit in Russia with such high quality gems. Plagued by sporadic production and a lack of gem-quality crystals, Russian Demantoid remains expensive, rare and difficult to obtain, especially when calibrated for jewelry.

Durability & Care

Russian Demantoid (Mohs’ Hardness: 6.5 – 7) is an excellent choice for everyday jewelry. Russian Demantoid should always be stored carefully to avoid scuffs and scratches. Clean with gentle soap and lukewarm water, scrubbing behind the gem with a very soft toothbrush as necessary. After cleaning, pat dry with a soft towel or chamois cloth.

Map Location

Click map to enlarge